(Reuters) – Two years after seizing the country’s biggest energy company from Spain’s Repsol, Argentina hopes a new compensation deal will lure more foreign investment to what many believe to be some of the world’s most promising shale oil and gas prospects.

But the deal ending a bitter dispute between Argentina and the Spanish oil company may prove only a first step in dispelling investor concerns about economic conditions and energy policy in the South American country.

Repsol on Tuesday announced that its board of directors had approved a $5 billion settlement with Argentina after President Cristina Fernandez expropriated 51 percent of Repsol’s stake in energy company YPF.

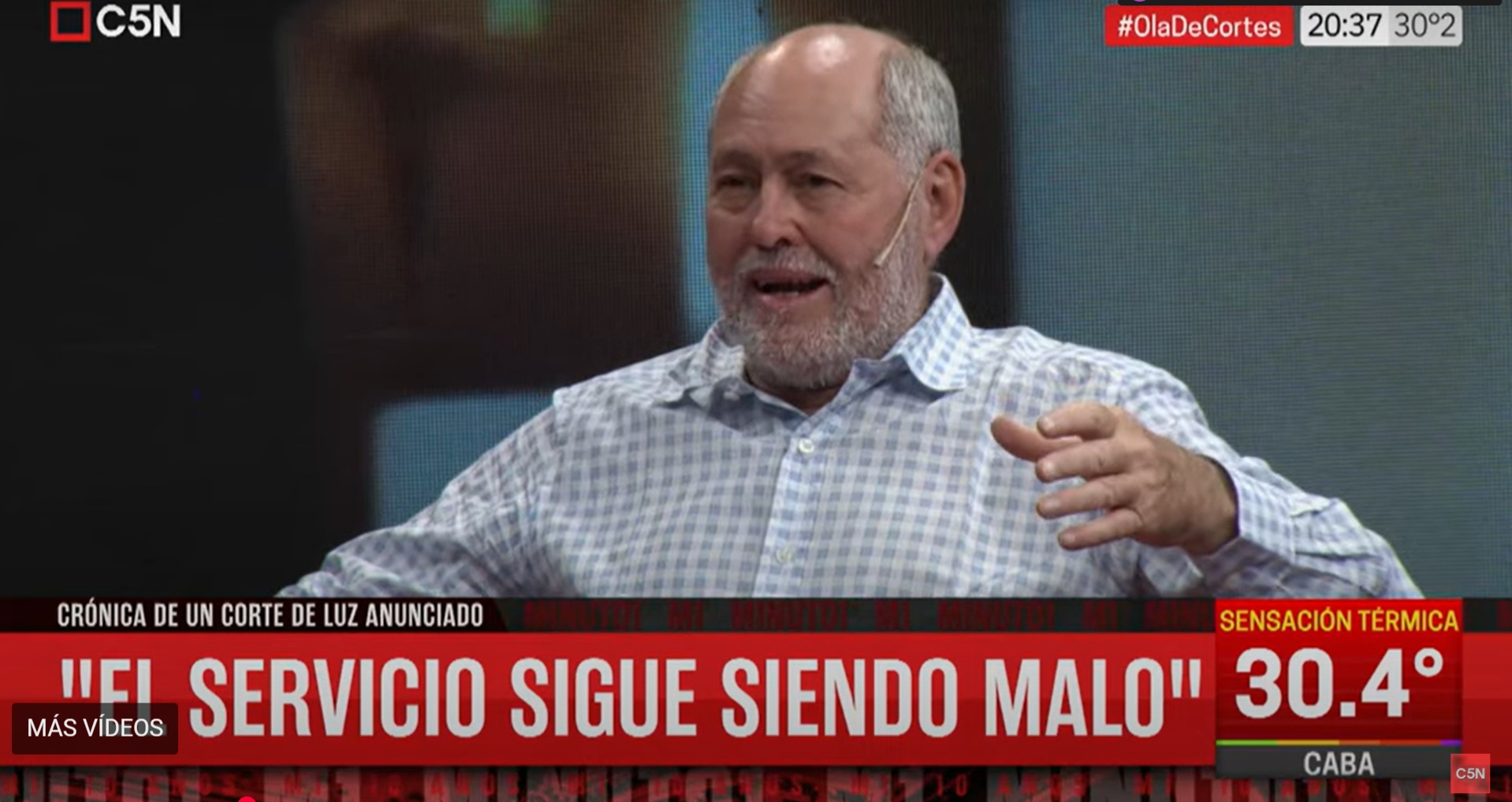

«The world can accept that a government takes an oil company into state hands, but only if you pay for it,» said Victor Bronstein, a Buenos Aires-based oil analyst.

Fernandez is betting the settlement will clear the way for Argentina to pursue investments from international oil companies to develop Vaca Muerta, Spanish for «Dead Cow,» a formation in the country’s Patagonia region that potentially holds one of the world’s biggest shale reserves.

«The agreement was absolutely necessary but it’s not enough to unleash a boom in investments,» said Jorge Lapena, president of the Institute of Energy General Mosconi and a former Argentine energy secretary. «What’s needed is a long-term energy plan, and the country doesn’t have that right now.»

Argentina is seeking financing and technological expertise to develop Vaca Muerta, but international investors, some worried about possible legal threats from Repsol before the announced agreement, have been reluctant to participate in large-scale development.

The success that Argentina achieves in attracting more companies to the mega field will depend on what steps the government takes to improve the country’s economic conditions.

For companies drawn to Argentina’s energy sector, significant challenges remain, analysts say.

They include the elevated costs of operating in a country with one of the world’s highest inflation rates and tough foreign exchange controls.

There are few signs those issues will be resolved in the near term. Fernandez, whose presidency ends next year, is struggling to contain inflation now running around 30 percent and to preserve Argentina’s dwindling currency reserves.

Analysts said the cost to develop a well at Vaca Muerta could run between $8 million and $10 million compared with between $2 million and $3 million in the United States, where shale drilling is already key to energy supplies.

That means Argentina will need to lure mammoth amounts of capital in order for the Vaca Muerta project to proceed more quickly. YPF has said it will need $250 billion to develop Vaca Muerta.

A U.S. Department of Energy report shows that Argentina has more natural gas trapped in shale rock than all of Europe, a 774-trillion-cubic-feet bounty that could transform the outlook for Western Hemisphere supply.

The country’s shale gas reserves trail only China and the United States.

Fernandez has billed the YPF takeover as a fresh start for Argentina’s energy industry, which has seen a decline in recent years in oil and gas production and the country’s hydrocarbon reserves.

The drops in production and reserves have triggered a chronic energy deficit in Argentina, meaning energy imports exceed exports, putting pressure on government coffers.

In 2012, Argentina raised natural gas prices at the well in an attempt to encourage increased production.

Since Fernandez’s decision to seize YPF, the government has signed one major Vaca Muerta deal, a $1.24 billion joint venture with U.S.-based Chevron Corp.

Several other companies have signed on to smaller projects, including ExxonMobil, Total, and Royal Dutch Shell.

Earlier this month, YPF said it signed an agreement with Malaysian state-owned oil company Petronas for a possible investment in Vaca Muerta.

Brazilian oil company Petrobras said on Tuesday it is looking to boost oil exploration and production in Argentina.

To get the Chevron deal done, the government loosened its foreign exchange regulations for the company and also reduced import taxes on drilling equipment.

The energy institute’s Lapena said the government needs to lay out broader policies to help more companies have a clear understanding of the investment terms in Vaca Muerta.

«We can’t have a case-by-case policy, we need a general policy,» he said. (Writing by Kevin Gray; Editing by Jonathan Oatis)

Original: http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/02/26/argentina-ypf-idUKL1N0LV28I20140226